The world is full of amazing places and chances to see them are very small. There are so many fascinating ancient buildings in the world, which are worth seeing. All of them are unique, and they represent landmark for the place where they are located. Beside that, all of them have rich history. Check out below, and see the greatest historical buildings that we have chosen for you. Enjoy!

Banff Springs Hotel

Théâtre antique d’Orange

The Théâtre antique d’Orange is an ancient Roman theatre in Orange, France, built early in the 1st century AD.

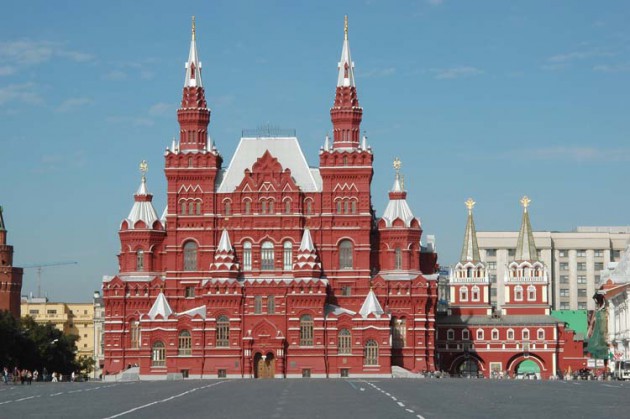

State Historical Museum

The State Historical Museum of Russia is a museum of Russian history wedged between Red Square and Manege Square in Moscow.

Bolshoi Theatre

The Bolshoi Theatre is a historic theatre in Moscow, Russia, which holds performances of ballet and opera. It was opened on January 6, 1825.

Source

Konark Sun Temple

Konark Sun Temple is a 13th-century Sun Temple at Konark in Odisha, India. It is believed that the temple was built by king Narasimhadeva I of Eastern Ganga Dynasty around 1250 CE.

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour is a cathedral in Moscow, Russia, and with an overall height of 103 metres (338 ft), it is the tallest Orthodox Christian church in the world. The first finished architectural project, was endorsed in 1817.

Source

St. Mark’s Cathedral

St. Mark’s Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Venice, northern Italy. It was completed in 1092.

Cathedral of Saint John the Divine

Cathedral of Saint John the Divine is the cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. Its construction started in 1892.

Source

Blue Mosque

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque or Blue Mosque is a historic mosque in Istanbul. It was built from 1609 to 1616.

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey or Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, is a large, mainly Gothic abbey church in the City of Westminster, London.

Mundeshwari Temple

The Mundeshwari Devi Temple is located at Kaura in Kaimur district in the state of Bihar, India on the Mundeshwari Hills. It was built between 105-320 AD. May be the oldest surviving (non rebuilt) Hindu temple in the world.

The Basilica of Constantine (Aula Palatina)

The Basilica of Constantine, or Aula Palatina, is located at Trier, Germany. It was built at the beginning of the 4th century.

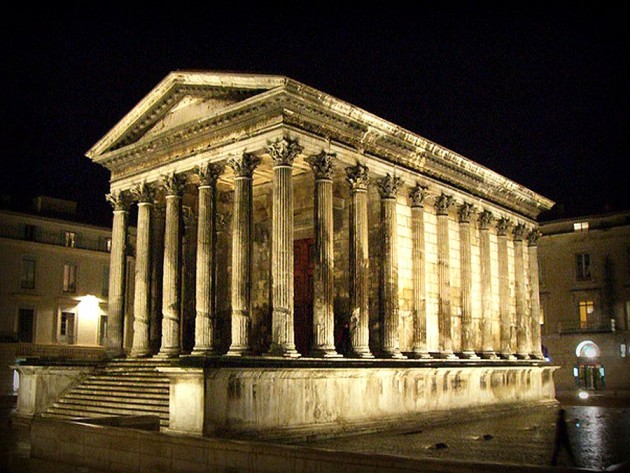

La Maison Carrée

The Maison Carrée is an ancient building in Nîmes, southern France- it is the best preserved Roman temple facade to be found anywhere in the territory of the former Roman Empire.

The Alhambra

The Alhambra is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. It was It was originally constructed as a small fortress in 889.

Source

Milan Cathedral (Duomo di Milano)

Milan Cathedral is the cathedral church of Milan, Italy. Its construction started in 1386.

Acropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens is an ancient citadel, located on a high rocky outcrop above the city of Athens, Greece. It was built at the time of the Mycenaean civilization.

Bodiam Castle

Bodiam Castle is a 14th-century castle, located near Robertsbridge in East Sussex, England. It was constructed in 1385.

Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal is a white marble mausoleum located in the Indian city of Agra. It was built from 1632 to 1653.

Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheatre)

Colosseum is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy. Its construction began in 72 AD, and was completed in 80 AD. After that were made several further modifications.

Porta Nigra (Black Gate)

Porta Nigra is a large Roman building, located in Trier, Germany. It was built 186 and 200 AD.